For a committed writer, the act of writing is an essential part of one’s day. Regardless of whether the currents are flowing or not, the work is to be done, the thought is to be activated, the presence of the muse is to be beckoned, if not implored. And yet the dryness, the aridity is as an ever-present shadow, if not in the foreground, then lying in wait between sessions, within sessions, beyond sessions. Committed dailiness is also integral to the life of the musician, the artist, the philosopher. One’s instrument is to be coaxed to expression daily.

This commitment is not limited to exterior acts. Our characters are not ready-made, but are shaped and reshaped throughout life. Even the barest measure of self-reflection reveals that we err, that we sin, that we do things in ways that cause regret, that we can do better than we do. So how are we to become free of error, to be done with sinning, to give what is truly needed in each situation, to do as well as can be done?

Philosophies, theologies, and moralities can be constructed around such considerations. There is human agency on the one hand. We may find ourselves in favourable or in adverse circumstances, and we can act and react in ways that either further or hinder our situation. On the other hand, we may feel ourselves to be acted upon by forces over which we have no control at all. Safe passage is not a given. Our acts will sometimes be fruitful, but at other times serve only to embroil us further. What is it to perceive clearly? To know when to act? When to desist? What are the foundations of right thought, of right action? Where are the fonts of wisdom?

A consistent thread that emerges in all traditions that address this problem is agreement on the need for daily reflection, for daily renewal. Once one is committed to examining, to testing the possibility of transforming one’s life, to developing discernment and skill in judgment, then the question of method arises. How is such needed change to be realised? Yet there is more at work here than mere method.

Beyond the immediate, there remains always the end towards which one aspires. Is it to live one’s earthly life well and to take one’s leave well-reconciled? But what is it to live well? And to what are we to be reconciled? All of this rests on more than simply doing things better. What traces are to be left of our own lives? What of our effects on the lives of others? What is the Kingdom of Heaven? Are we called to attain the Kingdom of Heaven? Are we to call the Kingdom of Heaven to earth? Can we call the Kingdom of Heaven to earth, or is this something beyond human agency? Such questions call for answers, yet the answers cannot be simply given. We can, however, learn to trust.

Perhaps we must ultimately learn to trust if we are to somehow escape the circularity of trying to think our way through that which lies beyond thought.

THE CURIOUS JOURNEY OF ALASDAIR MACINTYRE

In his latter decades, the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre gave such questions much thought, and in the process arrived at a position that is decidedly against the grain. As a young man during the 1950s, MacIntyre was a committed Marxist thinker and an active member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He served as an editor of the journal International Socialism from 1960 until 1968, seeing within Marxist ideas a possible means for not only understanding the human dilemma, but of securing social and economic justice for the many. Though born into a Scottish Presbyterian household, he became an outspoken atheist during the 1960s.

Karl Marx’s position on religion is both explicit and hostile. Marx wrote in 1843:

“[T]he criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism. . .

The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man. Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. . .

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. . .

The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself.” [1]

As his enthusiasm for Marxist thought began to wane, he immersed himself in an intense study of Christian theologians and intellectuals. His long-standing Aristotelian affinities found a new home in the intricate but well-ordered labyrinth detailed in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas. Such inquiries ultimately led to his conversion to the Catholic faith when he was in his fifties. Catholicism and its underlying principles thereafter became integral to MacIntyre’s philosophical position.

This peculiar path to faith seems strangely appropriate for one of MacIntyre’s temperament and disposition. His entry into the Catholic church followed an intense philosophical engagement with one of the greatest Catholic thinkers whose method was grounded in a deep explication of Aristotle’s ideas. St. Thomas Aquinas’s spirituality consisted, however, in more than a reformulation of Aristotelian ethics. As a young man in his twenties, Aquinas had studied under Albertus Magnus whose writings on antimony and other minerals reveal him to have had a deep knowledge of European alchemy. The young Aquinas may well have participated in the illuminated life-world of his teacher and mentor, and his later work would have been informed as much by his experience of a spiritually charged reality as by rational intellection. No surprise that Aquinas continues to be remembered as the Angelic Doctor.

FROM MARX TO JESUS

MacIntyre delivered a lecture entitled Catholic Instead of What? at the University of Notre Dame in November 2012. [2] He was 83 years of age at the time. It was impressively clear during his presentation that deep and sustained thinking throughout his life has not done him any harm.

In this lecture, MacIntyre affirmed his

commitment to Catholicism and the centrality of Revelation, particularly as mediated by Jesus in the Gospels, in

his view of the world. He thereby placed himself at odds with most of his

colleagues within the academic establishment. Early in the lecture, he stated:

“To

be a Catholic here and now is to reject, among other things, the claims of any

version of scientific naturalism. . .

Scientific naturalists are atheists, since no finding of physics,

chemistry, or biology provides them with anything like a good reason for

asserting that God exists. . . To study nature as physicists, chemists, and

biologists study it is already to have excluded God from the possible objects

of inquiry.”

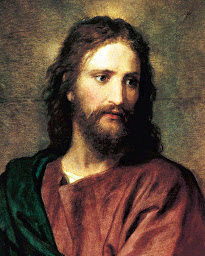

MacIntyre’s Catholicism seems to have been won by dint of the logical coherence of Aquinas’s method tempered by a personal acceptance of the Christian revelation. Yet his sense of Jesus remains highly abstracted. It does not appear to be based on the experiential reality made manifest in the lives of St. Francis of Assisi or Padre Pio of Pietrelcina - both of whom carried the marks of the crucified Christ - or of the many saints throughout history who claim to have engaged mentally and materially with the person of Jesus. Such experiences are abundantly described in the writings of Teresa of Avila, Faustina Kawalska, and Alexandrina da Costa among others. MacIntyre’s Jesus is second-handed through such interpreters as Geza Vermes who writes of the Jewish Jesus, J.D. Crossam who describes the egalitarian, peasant Jesus, Albert Schweitzer who addresses the eschatological Jesus, and the historicised Jesus reconstructed by Anglican bishop N.T. Wright. Regarding these various representations of Jesus, MacIntyre asks:

“In which Jesus are we to believe? Among these contenders, only the last [that of N.T. Wright] is recognisable as the Jesus of whom the Catholic church speaks, or rather, the Jesus who speaks to us through the Catholic church.”

MacIntyre at least acknowledges the fact that the Jesus of which the Catholic church speaks actually speaks through the Catholic church itself and through its saints - those chosen by Jesus to carry the message of his living truth to those in this world. Curiously, MacIntyre strongly inclines towards the image of Jesus presented by N.T. Wright despite the fact that Wright himself has not been shy in declaring his soft hostility towards Catholicism. Not only is Wright intellectually opposed to the notion of Purgatory, but he has little time for Marian devotion. In a presentation given in Edinburgh in 2003, Wright made his position completely clear:

“I am horrified at some of the recent Anglican/Roman statements, for instance, and on things like the Papacy, purgatory, and the cult of saints (especially Mary). I am as protestant as the next person, for (I take it) good Pauline reasons. But justification by faith tells me that if my Roman neighbour believes that Jesus is Lord and that God raised him from the dead then he or she is a brother or sister, however much I believe them muddled, even dangerously so, on other matters.” [3]

Even though the notions of Revelation and Faith figure prominently in MacIntyre’s stated position, the world somehow seems to win out in the end. Does the old Presbyterian in him still have the last word? Has the old Marxist really been shaken off? Perhaps there is something suggested here about the tenacity of old complexes despite our strongest attempts to put them behind us.

On the other hand, what does come through in MacIntyre’s presentation is a complete acceptance of the promise held in Catholicism, the promise of passage beyond any given life, beyond time and matter, beyond the fallenness of the human condition. This is the sustaining hope that overcomes the emptiness of the atheistic vision within which we somehow take on material form, spend our days running the gauntlet of life’s perplexities and ultimate meaninglessness, only to dissolve back into the elements that formed us when we breathe our last.

OF DEEPER HOPE

The role of Hope is central for MacIntyre. He states:

Li Zhisui, the doctor who attended Mao Zedong during his final sickness offers a less ample view of hope and its nature. He reports the following:

For one fully grounded in the historical materialism outlined by Marx and Engels, and for one fully committed to atheism, the only hope that can be envisioned is one based in human existence. There is simply nothing beyond one’s final breath. As Li Zhisui said, all was finished. Yet from the perspective taken by MacIntyre and many others, death is not an ending, but a source of hope, a promise, an anticipation, a new beginning.

Mao’s revolution did away with the outer cultural forms and the social structures that were integral to China for several millennia. It also discarded and disregarded much that was integral to the Chinese psyche. The Taoist understanding is emblematic of Chinese thought. It infused and continues to infuse the lives of Taoist recluses, Confucian scholars and many throughout China who have managed to avoid or escape the progressivist technocratic treadmill imposed in recent decades. Much has also been transmitted through the Buddhist tradition and incorporated into deeper Chinese cultural understandings. And the Catholic missionary monks who have been active in China since the 7th century have quietly made their own mark.

In all of these traditions, hope is not something that is summarily extinguished by death. For both Taoist and Buddhist, death offers the means whereby one’s circumstances may be improved through a more favourable re-birth. In the Catholic vision, unless one damns oneself through obstinacy, wilfulness, and a conscious choice of evil over good, after death one enters a different mode of being wherein one undergoes a period of purgation before attaining the beatific vision in which we come to apprehend our creator in eternity. This belief, and for some, this certainty is the source of hope that provides a sense of purpose, of continuity and of fulfilment for what may be only shadowy presentiments while yet we are in the world.

If one cares to look sufficiently into the

lives of those who have transcended human limitation - the saints, the sages,

the prophets, and the magi of every culture - it is clear that there is far

more to the picture than that which has been corralled into the constricted and

self-limited world of materiality and rational agency. This is a questing that

can never be resolved by disputation and argumentation, but only through

experience, grace, trust and an openness to that which is above and beyond

one’s own powers and one’s own will.

CATHOLIC INSTEAD OF WHAT?

Below is a video recording of the lecture given by Alasdair MacIntyre at the Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture in November 2012.

NOTES

1. Introduction to “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right.” Available online at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm (emphases in original)

2. Video of the presentation is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XjYLM1lw47Q&t=1s and a full transcript is available at: https://chamberscreek.net/library/macintyre/macintyre2012catholic.html

3. https://ntwrightpage.com/files/2016/05/Wright_New_Perspectives.pdf. See p. 19

4. This anecdote is

recounted from 1h 47m 40s to 1h 49m in the second part of a two-part

documentary of the revolutionary transformation of China between 1911 and 1976.

It can be accessed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJyoX_vrlns

Vincent Di Stefano M.H.Sc., D.O., N.D.

Inverloch, July 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment