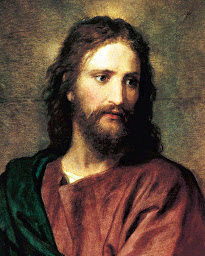

Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, the Capuchin priest who carried the wounds of

the crucified Christ, embodied truths that have been stridently denied

by many who would tell us how to think and what to disbelieve during

these times of overwhelming power and overwhelming impotence. This

remarkable man bore witness to the essential truth carried in the

Christian understanding of the Incarnation, of the human embodiment of the living Christ. As one who bore the stigmata,

the five wounds of the crucified Jesus, Padre Pio projected historical

truth. He shares this witness with others such as Saint Francis of

Assisi, Therese Neumann and more recently, Filipino visionary and

mystic Emma de Guzman, each of whose lives has challenged the illusory certainty of what has been deemed the limits of the possible.

Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, the Capuchin priest who carried the wounds of

the crucified Christ, embodied truths that have been stridently denied

by many who would tell us how to think and what to disbelieve during

these times of overwhelming power and overwhelming impotence. This

remarkable man bore witness to the essential truth carried in the

Christian understanding of the Incarnation, of the human embodiment of the living Christ. As one who bore the stigmata,

the five wounds of the crucified Jesus, Padre Pio projected historical

truth. He shares this witness with others such as Saint Francis of

Assisi, Therese Neumann and more recently, Filipino visionary and

mystic Emma de Guzman, each of whose lives has challenged the illusory certainty of what has been deemed the limits of the possible.

We pride ourselves on the cogency of the scientific knowledge and

understanding that have enabled us to crack apart both atoms and atolls,

leave flags and footprints on the moon, and map the structure of

cellular DNA and viral RNA. This same pride has decreed that only

through such methods as those sanctioned by science can we arrive at Truth. But despite our declared certainties, there is much within human experience that continues to defy scientific interpretation.

Sixty years ago, historian of science Thomas Kuhn

described how our ways of thinking can become so constrained that we

summarily dismiss or disallow all facts that do not conform to the

paradigm through which we interpret the world and our view of how the

world should be. Kuhn describes how the progressive accumulation of

"anomalies" that do not fit in to our preconceived theories can force a

complete re-evaluation of the paradigm or model through which phenomena

are understood and interpreted. According to Kuhn, this process

underlies the periodic revolutions that transform scientific

understanding.

There is no shortage of "anomalous" manifestations in the world. There

is much that occurs in the experiences of many that simply cannot be

accommodated by a materialistic and rationalistic view of reality.

Padre Pio of Pietrelcina first received the stigmata, or the marks of

the crucified Christ on his hands, feet, and chest when he was in his

twenties. As a novice and young monk, he had engaged in a number of

ascetic disciplines. His self-mortifications were, even according to his

teachers and companions, considered to be extreme. Within the history

of Christian asceticism, there have been many who, after the death of

Jesus, exerted themselves in ways other than by prayer and fasting. The

spiritual traditions of every culture acknowledge the transformative

power of intense ascetic discipline. Yet there are some who would

consider them to be severe aberrations of spirituality. Russian

Religious Philosopher Nicolas Berdyaev was highly critical of much

within the Christian ascetic traditions. [1]

He was particularly scathing in his attitude to the phenomenon of stigmatisation, which was first made manifest in the life of St. Francis of Assisi. Berdyaev writes:

"Eastern Christian mysticism is not interested in the life on this earth of Jesus Christ or in the idea of imitating his passions. The idea of stigmata is likewise foreign to it. . . Such phenomena as stigmata are unacceptable to Eastern thought. Nor do disease and suffering play such an important part as they do in Catholic mysticism." [2]

Berdyaev's

curt dismissal of what is, in truth, a providential gift and in the

case of many stigmatists, a willing participation in the sufferings of

Jesus as a conscious act of co-redemption, is questionable. As

self-nominated spokesman for the Eastern churches, Berdyaev may have

deemed stigmata as "unacceptable" but this does not alter the fact that

they are a part of spiritual reality. In the case of Padre Pio, the

stigmata are a re-presentation of the truths lived and the miracles

performed by Jesus during his time on the earth re-manifested in human

form for the benefit of many. The influence of Padre Pio has transformed

the lives of numerous individuals both during and beyond the confines

of his earthly life. His presence and his action showed him to be a man

of immense spiritual power and attainment. Padre Pio has clearly walked a

path reserved for but few souls on the earth. [3]

The early

letters of Padre Pio to his two spiritual directors explicitly reveal

the extent to which his spiritual practices brought him into contact

with demonic forces that literally made his life hell. [4] For Padre

Pio, the inhabitants of hell worlds were not the imaginative projections

of an inflamed consciousness, but actual presences with whom he

actively contended. Padre Pio perseveringly and unflinchingly pursued a

path that he had unexpectedly entered as a young man, a path that

reached an extraordinary culmination that he could never have fully

anticipated. Throughout his life, Padre Pio lived within the graces and

powers associated with the stigmata, while paradoxically experiencing

indescribable physical pain and torment.

His mission was also marked by extraordinary works. The creation of the Casa Solievo Della Sofferenza, a large hospital constructed in San Giovanni Rotondo during the 1950s was driven largely by Padre Pio from within the confines of his monastery. Despite his accomplishments in both the spiritual and material worlds, Padre Pio claimed no exalted status, but even to the end, expressed a surprising uncertainty about his own relationship with the Divine. His biographer C. Bernard Ruffin comments:

Incredibly, Padre Pio at times seemed to doubt that he was in a state of grace. "You have respect for me," he told a friend, "because you do not know me. I am the greatest sinner on this earth." Complaining that every good intention was marred by vanity and pride, he insisted, "I am not good. I do not know why this habit of Saint Francis, which I wear so unworthily, does not jump off me. . . . Pray for me that I might become good." [5]

This extraordinary comment was made

towards the close of his life. Yet even as a young man, a year after he

had received the stigmata in 1918, he confided to his spiritual advisor:

"I doubt at times whether I myself even possess the grace of God." [6]

Such reflections cast the reality of relativity into sharp relief. Padre

Pio clearly held many deep insights that elude most of us. He may have

been so conscious of the nature of perfection that the minor weaknesses

with which every one of us contend in the course of our daily lives

became, for him, a source of anxiety and self-recrimination. Perhaps the

self-expectation of those who have truly transcended human limitation

and who fully inhabit spiritual reality is beyond anything we can

comprehend. His own reflections in such matters may serve to awaken us

to the folly of complacency and the danger of self-satisfaction in

considering one's own relationship to the Divine.

Padre Pio of Pietrelcina represents yet another remarkable enigma born

of Italian Catholic spirituality. His life has served to reaffirm the

deeper values of love, healing and transformation carried by deep

Christianity during this broken time of materialism, nihilism and abuse

that subvert and deny the essential truths taught and lived by Jesus of

Nazareth.

Notes

1. Nicolas Berdyaev (1939): Spirit and Reality

(trans. George Reavey), Geoffrey Bles, The Centenary Press, London. See

especially Chapter IV: "The Aim of Asceticism" pp. 69-93

2. Ibid., pp. 141-142

3.

The meaning of the life of Padre Pio cannot be encompassed simply by

knowing his story or the range of his spiritual gifts. It is only in the

context on his day-to-day influence on the lives who knew him and loved

him that one can begin to form a coherent understanding of the man and

his mission. the reminiscences of those who were close to him will

provide far more light than any formal examination of the many available

histories and commentaries. For one such account, see: https://lavianuminosa.blogspot.com/2018/02/in-presence-of-transcendent-giuseppe.html

4. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina. Letters, Volume I. Correspondence with his Spiritual Directors (1910-1922),

Edizioni Padre Pio di Pietrelcina, San Giovanni Rotondo, 2012. Accounts

of Padre Pio's early encounters begin very early in the exchange of

letters with his directors, the first intimations being recorded in his

letter to Padre Benedetto on 6th July 1910. (p. 211) Numerous highly

graphic accounts of his experiences follow throughout the 12-year period

of correspondence.

5. C. Bernard Ruffin (1991): Padre Pio. The True Story, Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, Huntington, Indiana, p. 373

6. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, Letters, Vol. I, (op. cit.), p. 1284

Vincent Di Stefano D.O., M.H.Sc.

March 2014

Revised September 2021

A Prayer for Healers

by Padre Pio da Pietrelcina

O divine healer of bodies and of souls, Lord Jesus, Redeemer, who during your life on the earth cared for those who were afflicted and healed them with a touch of your all-powerful hand, we who are called to the difficult mission of healing adore you and recognise in you our sublime model and source of strength.

May you ever guide our minds, our hearts and our hands so that we may deserve the praise and honour bestowed by the Holy Spirit upon our vocation.

May there awaken within us a growing awareness of our role as your collaborators in the protection and the development of humanity, and of our role as instruments of your divine mercy.

Illuminate our intelligence in the pursuit of an understanding of the pain and difficulties caused by the numerous afflictions that can assail our bodies until, by skillfully availing ourselves of the findings of science, the causes of sickness no longer remain hidden to us. By your grace, may we be neither deceived nor mistaken regarding the nature of our patients' symptoms, but with sure judgement, select the best remedies or treatments that have been made available through your Divine Providence.

Fill our hearts with your love and help us to recognise your own self within our patients, particularly those who are most wounded and helpless. May we respond to the trust that they have placed in us with the utmost care and energy.

Imitating the example you have set for us, may we be parental in our concern, sincere in our advice, diligent in our ministrations, strangers to deception, and wise in our discernment of the mystery of suffering and of death. Above all, may we be constant in our defense of your sacred law of respect for all life against the assaults of our self-serving and perverse instincts.

As healers who give glory to your name, we vow that our activities will be continually guided by moral righteousness and that our lives will honour the laws of morality.

Finally, grant that we ourselves, through the Christian conduct of our lives and the just practice of our profession, may one day be worthy to hear from your lips the blessed words that you have promised to those who have ministered to you in the form of those who are in need: "Come ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world." (Matt. 26, 34)

May it be so !

Original Italian Version

"Pray, Hope and Don't Worry"

A documentary examining the life of Padre PioRELATED POSTS

1. In the Presence of the Transcendent. Giuseppe Caccioppoli and Padre Pio of Pietrelcina

The meaning of the life of Padre Pio cannot be fully encompassed by knowing his story or the range of his spiritual gifts. It is only in the context of his day-to-day influence on the lives of those who knew him and loved him that one can begin to form a coherent understanding of the man and of his mission. The reminiscences and stories of those who were close to him will provide far more light than any formal examination of the many available histories and commentaries that attempt to describe his life and detail his attributes. One such story is offered by Giuseppe Caccioppoli, a spiritual son of Padre Pio.